This is a tale of my first trip (and many thereafter) to Spiti Valley and Kinnaur. Like most first trips to new lands, planning this one had moments of less expectations and more apprehensions. It had been raining quite heavily in the region I was heading off to, complete with landslide scares and more.

It was a time when Instagram had rare users in India; Google Maps was not a go-to (most of us did not know how to save offline maps and never bothered to learn it either); there were no live updates that one could have while on the road; you would not find anyone sporting a Leica or, for that matter, a 120 mega-pixel camera phone; the photos would come out blurry yet clearer in memory and the videos, pretty much shit.

I had just bought a Canon 600D with my office bonus, and both the camera and I commanded equal respect from anyone needing a photo.

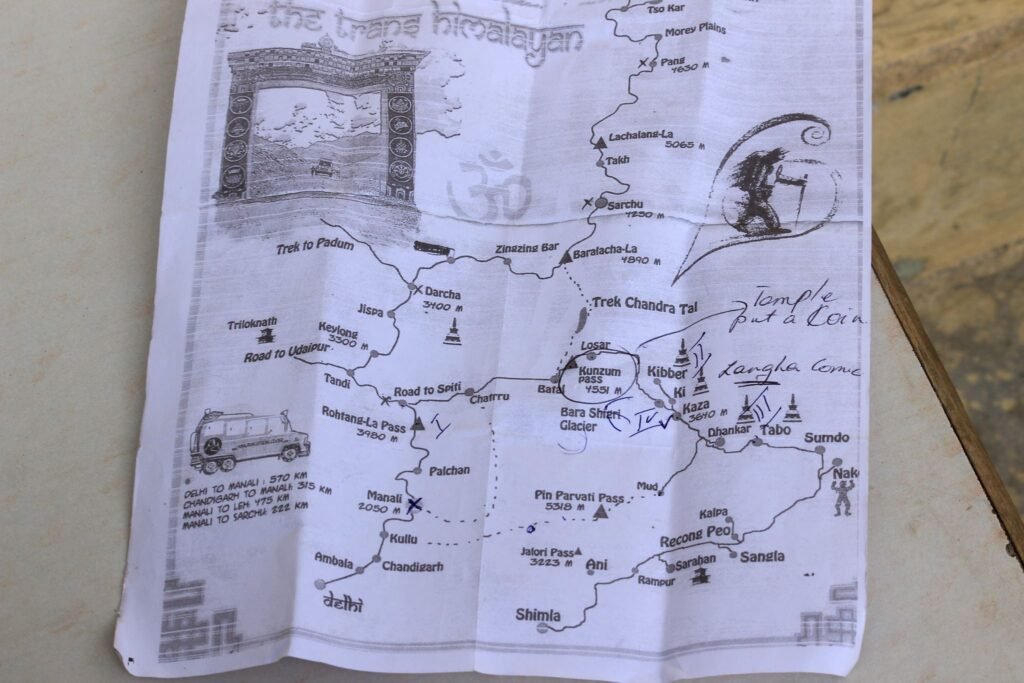

It was not the time to record, it was the time to live—to try and read paper maps correctly, to seek locals’ advice en route, to move with no fixed itineraries and to not read (or write) 15 Places To Visit…. sort of listicles, AI existed only for the likes of Geoffrey Everest Hinton, and nobody called coding a life skill.

I mostly lived on the road, and joyfully surviving was the only life skill that mattered.

So, I left on a bus to Shimla, where another friend waited with her old Tata Sumo. A car that looked like it would fall apart but it did not. We loaded our bags in, complete with my friend’s packet of fresh bread, loose tea leaves, apple jam and a lot of apricots. She was trying to go vegan back then, I survived on rajma-chawal mostly. She smoked beedis and I smoked Himalayan wind, we made a good team. I still cannot assure that we were well-kitted for the journey that awaited. If not for the headiness of our youth, we would have stayed put.

Every moment spent there is now a memory to cherish—the drive through wild water streams flowing all across the roads, walking down roads to get food while the rain poured, the silent prayers when the car wheels were more than half submerged in slush, plates of rajma-chawal becoming our main diet for days, running into a man who was an Everester, reading the numerous and humorous BRO (Border Roads Organisation) messages, watching distant stars grow into giant stars as the journey progressed.

In hindsight, I was on my first experiential, culture and community-driven, sustainable journey. Long before these words led businesses in search of a better way to travel. Here, sharing the magic of travelling in the Himalayas before the experience turned into a social media affair of the bad kind.

Shimla-Sarahan-Sangla, the joy of driving down Hindustan-Tibet Road

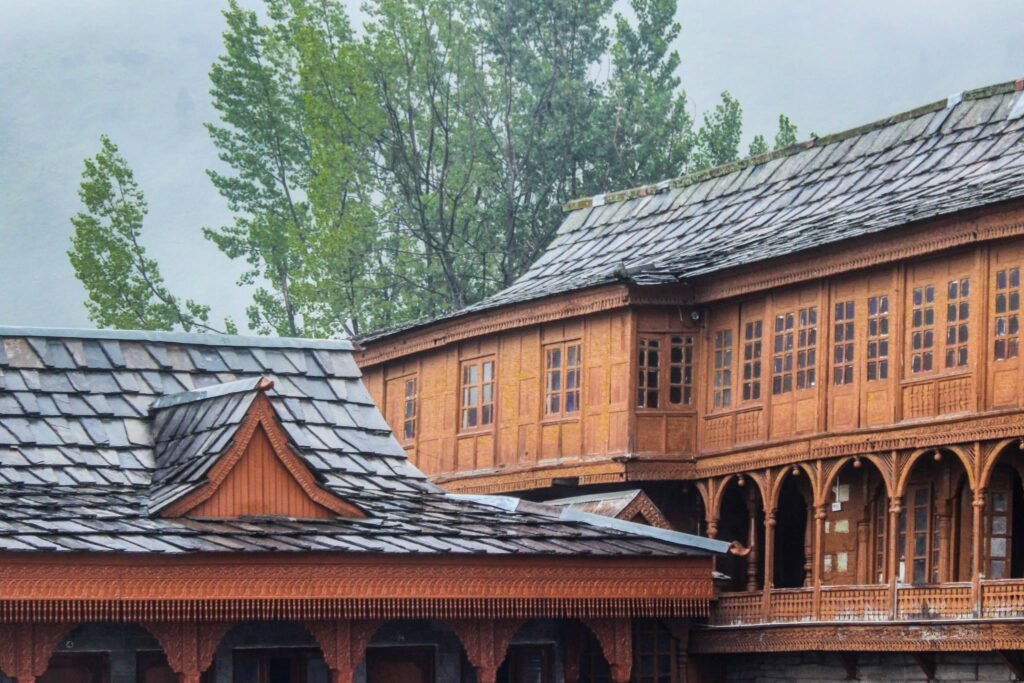

If you want to stay offbeat on this trip, I recommend an overnight stay at Sarahan before heading off to Sangla. The hamlet is home to Sarahan Bhimakali Temple, a very fine example of kathkuni architecture. We stayed in the temple premises, experiencing the rituals from close, fascinated by yet another different facet of life in the Indian Himalayas. A local family invited us to their wedding feast in the temple the next day, feeding us like one of their own.

We reached Sangla in the afternoon that narrowly escaped getting marred by heavy rains. It was so foggy that my wish to get the first glimpse of the astounding views that Sangla offers was unfulfilled. With no to-do list in mind, we explored the tiny hamlet.

We picked a short trail and reached the tiny yet gorgeous Kamru Fort, built mainly of rocks and wood. Strolling around, we reached the Badrinath Temple, and ran into dozens of Kinnauri women. Dressed in their traditional attire, complete with the green caps that they wear as a gesture of respect for Himachal Pradesh’s ex-CM Virbhadra Singh, lovingly called Rajaji for his connection with the royal family of the state. Drum beats could be heard in the distance as we flopped down on the rock-cut stairs of the temple to watch the ritual.

Dark, moody, magical—Sangla is all that and more when it rains. It would make you think of dense Himalayan forests and what all could they be home to.

To fairies and nymphs perhaps. To hermits and sages perhaps. To myths and lore we don’t know about yet. To deities and demons. To the wilderness in human hearts. To solitary longings and the basic of returning to the forests we once lived in.

An old rundown house in Sangla©Shikha Gautam

It was a fascinating sight, locals gathering to welcome their deity, some carrying his palanquin. And then, they danced, the Kinnauri naati dance. It was a sight that would live with me—as vivid as it was that day—not to be captured for an Instagram reel or YouTube but to be lived subtly and quietly.

I chatted away with the local women, who shared anecdotes, stories of the deity, infrastructure or the lack of it in the region, their kids, customary weather updates, and the advice that I should leave before it gets dark as the men, when drunk, get boisterous!

A shepherd by the riverside shared shards of local cheese, as we sat in silence and tuned ourselves to the roars of River Baspa.

It was long before Imitiaz Ali shot heartbreak by the same river; I agree that Chitkul might break your heart with the sheer beauty it has.

Chitkul in 2000s; away from most things modern. ©Shikha Gautam

We headed off to Chitkul the next day—a place with such dark forests that it reminded me of Bavarian woods—lush, dense, moody—with streams trickling down the mossy forest grounds. The place itself had a rundown inn back then, a far cry from the many hostels and hotels that Chitkul is now home to.

My first sighting of Kinner Kailash at Kalpa

Skies were a cobalt blue as we neared Kalpa. There were thick clouds rolling all around us and, somewhere in my mind, I was scared of missing a view of the majestic Kinner Kailash. Monsoon clouds weren’t helping as we drove through them from the gorgeously drenched Sangla and Chitkul. A lovely hamlet, Kalpa is one of the best places to watch the ranges; a fact easily fathomable from these photos. I still believe that Kalpa is the most beautiful place I have yet seen even after travelling to so many places that I have lost the count.

Kalpa is not a place for itinerary-driven trips. You might get bored in a day here or might never be over the place.

It is a place for slow experiences, watching the local life, school children scurrying off every morning, the local barber shop coming alive with village gossip, mongrels lazing under the Himalayan sun, clouds hovering over Jorkanden peak.

Sights like this are an everyday affair in Kalpa©Shikha Gautam

Watching the Sun go down the hills at Tabo

We were so famished and tired by the time we reached Tabo that when the waiters arrived with the food at the first restaurant in Tabo that they found us sleeping soundly.

Another group from Europe that was travelling with us was accompanied by their cook, and we understood why, for Spiti was not a place with lines of restaurants, dhabas, cafes or hotels that were also dine-in. It was tough to spot any such establishment for hours as we drove. We had our lesson and filled our car with dry food, bread and whatever we could find; only to have somebody break in at night and steal it all along with our trekking gear. That is the story for another time though.

The landscape wore a very fascinating golden look for the dipping Sun had put a colour filter on everything.

I had never seen such beauteous landscapes, it was one of those days that make you feel lucky. Even if it was just for an evening.

A friend and I watching the sun set over Tabo ©Shikha Gautam

Tabo is home to a Buddhist monastery that was built around 995 AD; this was one of the most well preserved monasteries I’ve ever visited. After visiting the monastery, we took the short trail to the painted caves at Tabo. Though I couldn’t found any paintings in there, the short trek brought me amazing views of the whole of Tabo. I could see the grey waters of River Spiti, the shocking green fields amidst the brown barrens, and tiny houses, all painted in white and brown. We stayed near the monks’ quarters in the monastery, an old wooden structure with washroom boards that creaked with every step. Yet the water ran hot and the place had all the hygiene checks in place.

We ate with the monks that night, surprised at how wonderfully they cooked! If you ever go to Tabo, I highly recommend eating at the monastery cafetaria for a meal that you would gleefully remember for long.

The first glimpse of Chandratal or the Moon Lake!

A high altitude lake (14,100 ft), Chandratal had been on my wish list for ages. Blue, yes it really is blue (!), water rippling in the middle of the high Himalayas was something that I cannot explain in words that are apt enough. This was no photoshop wonder. The drive from Kaza to Chandratal is tougher than it is today and anyone with a bad back might just skip it altogether. Alternatively, one can trek to the lake for an unforgettable experience. Unlike now, there were just two campsites at the lake, unless you wanted to pitch your own.

Our phone batteries were dead by now.

If anything like a power bank existed back then, none of us knew about it and we did not mind being off the network either. It would have made for a cosy stay if I had not dunked in the lake water the evening before.

But that’s perhaps what people who are born by a river do; can never resist a dip in cold waters.

The camping site at Chandratal on a rainy morning .©Shikha Gautam

Watching rain “happen” at Dhankar Lake

I write “happen” because rain had never looked like a phenomenon to me before this afternoon at Dhankar Lake, Spiti. AMS had hit me hard while I was hiking up to the Dhankar Lake. Though the trek was easy both in terms of terrain as well the distance (around 5 km from Dhankar Village), I was gasping for breath as the oxygen in the air ran thin.

The harsh Sun that was glaring down initially had given way to high-speed winds. I had to cover my ears to escape the almost deafening sound. Even then, I wasn’t expecting rains, for Spiti is a cold desert that rarely sees rain.

The huge rain drops that bombed me on the way up were thankfully carried away by the high speed winds. Yet, the lake water was turbulent and I could see the most fascinating phenomenon of rain formation across the lake. It looked like a dream. Or a 4D National Geographic show, airing on the hugest TV that you can ever imagine. Now that I look back, I wonder how viral this moment could have gone on social media!

Visiting Dhankar Monastery, cited as one of the 100 Most Endangered Sites by the World Monument Funds

More than the awe-striking beauty and surrealism of Dhankar Monastery, the fact that it’s an endangered site makes it a different experience.

Dhankar Monastery sitting pretty & treacherous.©Shikha Gautam

Though efforts are on to aid its conservation, the monastery is nearing a break down. More so because of its location. Built more like a fort, Dhankar Monastery stands true to its name, for Dhang means cliff while Kar stands for fort.

A 5 km trail from here leads you to Dhankar Lake, nestled from all sides by the high Himalayas.

We stayed at a homestay in Kaza, and would roam around in the local market for evenings. With little to no crops in the region, it was a surprise that Kaza had cafes that would dole out fresh salads, pita breads, freshly-brewed coffee, hummus-laden meals and what not. Solar power had become a thing here, much before rest of the country adapted to it and we would watch locals put batteries, torches, solar lamps out in the sun every morning. It was a ritual that nobody ever skipped. Kaza, back then, was on the verge of coming up with its first greenhouses for fresh produce.

Traversing across the most treacherous roads in the world!

The best experiences of a Kinnaur Spiti trip unfold on the roads here. It’s a very different thrill from any other road trip, for you have boards by roadside that read “You’re travelling on world’s most treacherous road”! But then, there were no roads to be found on some of the stretches. As you leave Kinnaur and enter Spiti, the roads are mostly rocks and soil.

Forget the word “metalled”. In mid-2000s, you had a back-breaking journey. This was also where I ran into the lady running my homestay sprawled on the stairs, cleaning the insides of a sheep, for a feast later in the day. It was perhaps the first time that I did not feel revolted at such a sight for life around here was evidently tough, with little to no scope of agriculture. If you wanted to make food for the masses, you would have to kill. Of course, it has changed much over the years now.

Watching Cham Dance

©Shikha Gautam

Masked dancers, dancing to the tunes of traditional Tibetan instruments, took the centre stage at the govt school ground by the side of Ki Monastery. It looked like a scene straight out of some carnival, complete with hawkers.

My first trip to Kinnaur and Spiti Valley was in search of stories, of the land and its people, their culture and rituals, the topography and lives that it supports. It would not suffice to write that I found it all, for there was more—there was warmth and magic. It was a land of shocking wilderness before over tourism did what it does best—give people access to pristine lands that have been long protected by the locals. People who have left behind their traces—from plastic bottles to beer bottles strewn on treks to plastic bags.

Kahaani Studio arranges locally-led trips to Spiti Valley and Kinnaur. We partner with local communities, homestays and hospitality partners while ensuring slow, comfortable trips.

Drop us an e-mail at Editorial@KahaaniStudio.com for details.

![They say it’s going to be a harsh summer.

We say it’s going to be a chilly vacation!

Our favourite pick of South India’s most offbeat hill stations.

[summer, travel, India] They say it’s going to be a harsh summer.

We say it’s going to be a chilly vacation!

Our favourite pick of South India’s most offbeat hill stations.

[summer, travel, India]](https://scontent-bom5-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.75761-15/491447958_17906810376140553_82115311286037935_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=111&ccb=7-5&_nc_sid=18de74&efg=eyJlZmdfdGFnIjoiQ0FST1VTRUxfSVRFTS5iZXN0X2ltYWdlX3VybGdlbi5DMyJ9&_nc_ohc=FFF6x3bUD6gQ7kNvwEfWqCu&_nc_oc=Adnl5zpuT8TVUK5pB0tuuHG0MeSzPBTEHgBLVXzVNIKuIvjMFV9QBFvED2noVqSPqDQ11MhUKoW6mk6l6li48-gO&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-bom5-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=ANo9K5cEAAAA&_nc_gid=1hHgOdMglMiZrcPniT8Vbw&_nc_tpa=Q5bMBQEwmEkoz12ANn4IQoes1xJYvO2caSUDBLJvDsWqZEADcOQWwZCC977FvRg5xP3c1lEQctu6VXrq&oh=00_AftH6IgTm0v9_Stk4-cSoacJZPbc6D3kK5JsVuKmdFYqRg&oe=69A8C477)